Working on Hard Problems

For me, 2025 has been the Year of Boggle. It started off as a revival of a 15 year-old project in an attempt to learn how to combine Python and C++. It turned into a months-long, all-consuming affair that eventually landed me on the front page of the Financial Times.

It’s always hard to call a project “done,” but my interest in Boggle has trailed off since this summer and I don’t foresee investing much more time in it going forward. So it’s time to write down my reflections on the whole process of solving a hard problem.

As a refresher, the “hard problem” was finding the highest-scoring Boggle board, and proving that it’s the best. This is difficult because of the vast number of possible boards. It’s quite unusual to work on a hard, open-ended optimization problems like this. The only other example I can think of in my ~20 year career is the algorithm behind Google Correlate.

So what did I learn? Here are a few highlights.

Success is just over the horizon

There are always many, many possible ideas to explore. But your time and energy are limited. How should you decide what to work on?

One approach is to prototype each idea a little bit, perhaps in Python. If an idea shows initial promise, you can spend more time developing it.

Unfortunately, this can lead to some really catastrophic decisions.

When I worked on Boggle back in 2009, I was excited about applying tree structures to the problem. I spent time implementing this approach in C++ and ironing out all the bugs. In the end, I only achieved a ~33% speedup over evaluating individual boards. This was disappointing, so I abandoned the idea and, in fact, the whole project.

Fast-forward to 2025, and I decided to investigate this approach again. I prototyped tree building in Python and got similar results. But this time, I optimized it a little further. The old code had two phases: one to build the tree and one to prune it. I had a TODO to merge these. This year, I did that. It was a huge win. The 33% speedup became a 2x speedup!

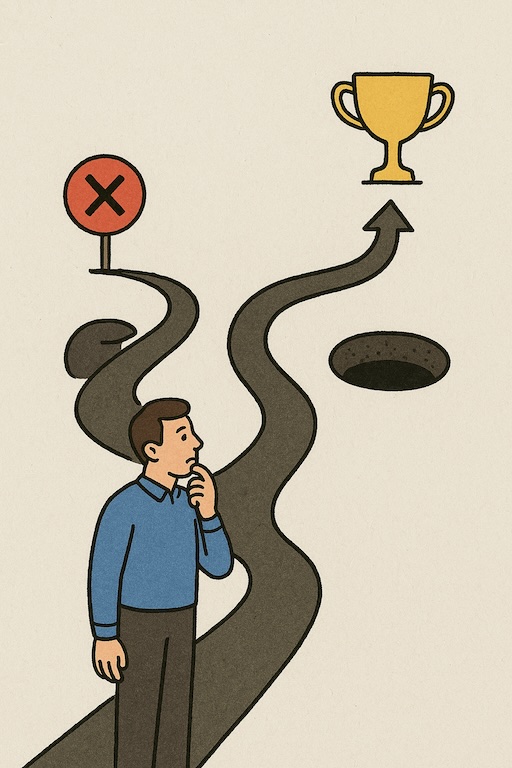

The spectre of that TODO loomed over the project this year. If my idea wasn’t panning out, was it because the idea was bad? Or was it just because I hadn’t pushed far enough on it? Was success just one small optimization away?

It’s impossible to know. That uncertainty is part of what makes these hard problems hard. You never know if you’re on the verge of a breakthrough or barking up the wrong tree. You don’t want to do 99% of the work and miss the 1% that makes it worthwhile like I did in 2009.

The Psychological Challenge

Working on a hard problem like this is intellectually challenging, yes, but it’s also psychologically challenging. You have an idea that you’re excited about. You implement it and spend time getting it correct. You port it to C++. And only then do you find out whether it’s truly a performance win.

If you spend a week implementing your idea only to find out it’s a wash, that’s really discouraging. But also… see above. Maybe there is a win, you just need to find one more tweak. Or maybe it’s really a dead end.

I think this psychological dynamic is why I abandoned the project back in 2009. This time around, I tried to be kinder to myself, and not get my hopes up too high about any particular idea. But it’s hard not to get excited. Coming up with new ideas that excite you is part of what makes working on a problem like this enjoyable.

This summer, I prototyped three ideas that I thought could be big wins, but none of them panned out. Hence my waning interest in the project.

Yesterday’s Good Idea is Today’s Baggage

You can’t hold on to ideas because they were a win at some point. Once you change something, you need to reevaluate your previous decisions. They may no longer make sense.

The big breakthrough that made 4x4 Boggle maximization possible was orderly trees. These were a win on their own, but fully capitalizing on that win required reworking nearly every other part of my algorithm. Ideas that I was proud of from earlier no longer helped and had to be abandoned. You can see this from the number of updates to my first blog post this year.

When I look at the repo and paper that resulted from this project, it doesn’t feel like a lot. Just 14 pages for six months of work! But you have to remember that this is just the tip of the iceberg, that the vast majority of ideas and code didn’t pan out. In the end, I deleted at least 90% of the code I wrote.

The Value of Notes and Blog Posts

Back in 2009, I didn’t keep notes about my Boggle work, at least none that I could find. I did write blog posts, though, and those were extremely helpful for me this year as I tried to understand all the code I’d written back in 2009.

You tend to write blog posts about things that work, though, rather than ideas that you abandoned. But reconstructing why an idea didn’t work can be important, too, and can save you a lot of wasted time. This time around I tried to track ideas in GitHub issues, and I’ve left notes about why ideas didn’t work.

I also kept daily notes on the project in a Notion doc. This doc wound up getting enormous, nearly 200 pages by the end of the project. (It got big enough that I had to split it up to keep Notion from bogging down!) This doc allowed me to reconstruct my thought process on any particular day in the past.

I also wrote blog posts about Boggle this year. (Shout out to the Recurse Center Publication Accountability Group for the encouragement!) These were a helpful way to summarize what I’d done at a high level, and they encouraged me to create visualizations. These visualizations were a helpful explanatory tool, but they also helped me understand what I was doing. “Fortune favors the prepared mind,” and really understanding your problem is how you prepare your mind to have insights.

Discovering Prior Art

Boggle optimization is a somewhat well-known problem, but I’m not aware of anyone else who’s attacked my exact problem of proving the global max.

Still, there were four cases where I learned that something I was doing had a name or mapped onto some other problem:

- Branch and Bound. I’d heard of Branch & Bound but never knew what it was. At some point this winter, I read the Wikipedia article on it and realized that this was exactly the approach I took back in 2009! Knowing that my algorithm had a name was helpful for explaining it to others, but it didn’t lead to any breakthroughs. This would prove the rule.

- BoggleMax is NP-Hard. I’d had a sneaking suspicion that there was some clean, fast solution to my problem that I was just missing. I had some uninformative conversations with ChatGPT about it, and I also asked about it on Stack Overflow. Eventually I got an answer: not an algorithm, but a proof that my problem was NP-Hard. On some level, this was frustrating: there was no easy answer! But it was also liberating. Since there wasn’t any easy answer, all my ad-hoc, problem-specific algorithms were the best way forward. I was freed from my “sneaking suspicion.”

- Binary Decision Diagrams. BDDs are a data structure from the 1980s. They’re famous, but I’d never heard of them. They turn out to be related to the trees I build for BoggleMax. In particular, they have a similar insight about making decisions in a well-defined order to produce a more efficient tree. As with Branch & Bound, learning about Binary Decision Diagrams helped to explain my algorithm but didn’t lead to any insights or speedups.

- Evolutionary Strategies. My hillclimber uses an ad-hoc strategy I developed that seemed to work well for Boggle. I later learned that this is properly called an Evolutionary Strategy (ES). Some of the rules of thumb around ES did help me speed up the hillclimer.

ChatGPT was very helpful for pointing me at prior art. Learning that an algorithm or data structure had a name was validating, but ultimately never led to any breakthroughs. My algorithms were already pretty well-adapted for my problem.

LLMs Can Help… Sometimes

I started the year pessimistic about coding assistants. GitHub copilot could be helpful for doing simple tasks, and I would occasionally ask ChatGPT to implement more complex algorithms for me. But I did almost all the coding myself.

In June, I decided to try Claude Code. I’d been wanting to restructure nodes in my trees, but I’d put this off because it seemed tedious and error-prone. I figured GitHub Copilot and ChatGPT wouldn’t be helpful because they’d get it wrong the first time and I’d have to debug.

My first experience with Claude was memorable and impressive. It also got it wrong on the first go, but it was able to figure that out based on compile errors and failed unit tests, and fix its own bugs. I still had to do some cleanup work, but this got me through the tedium.

Since this project was all about optimization, I figured I’d just ask Claude to optimize my code. I gave it a benchmark command and set it loose. After around ten minutes, it came back with:

The exercise demonstrates that this codebase is already quite well-optimized at the implementation level, and further performance gains would require algorithmic innovations rather than micro-optimizations.

So my code has the Claude seal of approval!

At the moment, I’m finding Claude most helpful for work that you know how to do, but are putting off because it’s tedious. Claude can do the initial implementation, which is often enough to get you past this phase. In this way, it’s like having a coworker on the project. When you’re at an impasse, they can help you make progress and get momentum again.

It’s not very good at open-ended tasks, but perhaps this will change in the future.

Conclusions

It’s hard to call a project “done.” There are always loose ends and unexplored paths. But I feel pretty done with Boggle. My goal at the start of the year was to learn how to combine Python and C++, and to solve 3x4 Boggle. I’ve done both of those, and I solved 4x4 Boggle and got some international headlines in the process!

Working on an open-ended problem like this has been hard, but also rewarding. There’s something exhilarating about knowing that the only thing standing between you and success is the ability of your mind to come up with new ideas. I didn’t know that success on 4x4 Boggle was even possible at the start of the year, but I’m happy it was!

Please leave comments! It's what makes writing worthwhile.

comments powered by Disqus